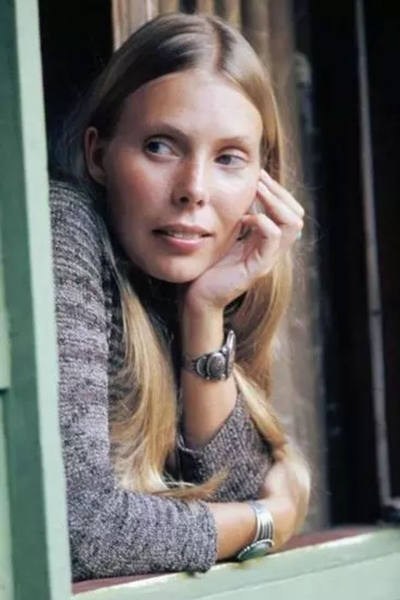

Photo by Henry Diltz

For many, the formative period of Joni Mitchell’s career, from the late 1960s to the late 1970s, is a countercultural Camelot fantasy. She’s the princess with the cheekbones, the flaxen hair, and a musical gift that set birds in flight across the kingdom. And she is pursued over the years by a round table of eager suitors with guitars — David Crosby, Graham Nash, James Taylor, Leonard Cohen, Jackson Browne, and J.D. Souther among them. But she will not be owned, this visionary and uncompromising woman, and she will become the legendary ruler of House Blue.

Or something like that. As with many origin stories, the history of Joni Mitchell has become a romanticized little movie, one that, no doubt, will appear someday on a screen near you. There will be the folkie ingénue fresh from Saskatoon, the baby she gave up and later found, the jazzy genius, the remarkable painter, and, at the end, the opinionated dowager. There will be the bitter break-up songs and the aching love songs, along with the identities of their fallen heroes — “Coyote,” about her encounter with Sam Shepard during Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue, for example, and “A Case of You,” about early lover and influence Cohen. Mitchell’s legendary life will be shaped into a period biopic with miniskirts, Laurel Canyon, two cats in the yard, and, at points, enough cocaine to fuel long lyrical explorations such as “Song for Sharon” and “Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter.”

That well-known narrative, capped by the angry political Joni who challenged but never alienated her loyal listeners, is essentially the outline of David Yaffe’s new biography, “Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell.” The book is a pleasant journey through the handed-down tales we’ve already heard, peppered with a few perhaps lesser-known vignettes — that Dylan wrote “Tangled Up in Blue” after a weekend listening to “Blue,” that Jimi Hendrix was a fan who, in his diary, called Mitchell a “fantastic girl with heaven words,” that Miles Davis once came on to her, flying “off the couch with his hands around my ankle — and passed out.”

There are no new twists, no deeper layers of detail that might further ground some of Mitchell’s well-known experiences. This portrait doesn’t try to be definitive or challenging; it’s comfort food for fans who can’t get enough of her brilliant career. If you don’t already know the particulars of Mitchell’s story — her upbringing as the only child of conservative parents, her bout of polio at age 9, her discovery by Crosby, who took pleasure in introducing her to the likes of Eric Clapton and watching them melt as she sang — then Yaffe isn’t going to explain them to you. You might want to bookmark the Joni Mitchell Wikipedia page to supplement Yaffe’s account.

At one point, as an example, Yaffe notes that Mitchell began writing after a dry spell after filming “The Last Waltz” in 1976. “She had been sick for some time, in and out of the hospital,” he writes, not bothering to explain much more about it other than a later reference by Mitchell to abscessed ovaries. Likewise, the most detail we hear on Mitchell’s long relationship with percussionist Don Alias — who was black, triggering Mitchell’s parents’ racism — is that he beat her up. Other boyfriends, including Taylor and Donald Freed, with whom she spent time after her divorce from bassist and producer Larry Klein, get even less attention, no matter how important they may have been to Mitchell and her work.

The more original and inquisitive material in “Reckless Daughter” is Yaffe’s literary analysis of each Mitchell album, particularly those from her first, “Song to a Seagull” in 1968, which Judy Collins told Mitchell “sounded like it was under a Jell-O bowl,” through “Mingus” in 1979. Yaffe walks us through those songs he finds most representative, and along the way a sense of Mitchell’s precision and her dominance in production decision-making clearly emerges. She has little praise for the the men who produced with her over the years, with particular contempt for Thomas Dolby of 1985’s “Dog Eat Dog,” whom she calls a “[s]limy little bugger.”

Indeed, Mitchell’s bitterness surfaces repeatedly, particularly in her 2015 conversations with Yaffe, from her view of first husband Chuck Mitchell as her “first major exploiter” to her belief that Dylan was at times quite jealous of her. Some of her harsh comments are directed at Klein, as she and Klein argue through Yaffe about the circumstances around her 1986 miscarriage. But fans of Mitchell, now 74, are accustomed to her thunderhead of judgment, the way she wrestles with her ego. Her ferocity has helped her stay true to her creative vision all these years, despite the sexism all around her, and it has helped her redefine the role of women in music.

The book ends in 2015, when Mitchell suffers an aneurism and lies unconscious on her kitchen floor for three days. But, as Yaffe has made clear, no one will be surprised if she finds her way back from disability, her stubborn defiance once again winning the day.

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on November 9, 2017. (5979)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment