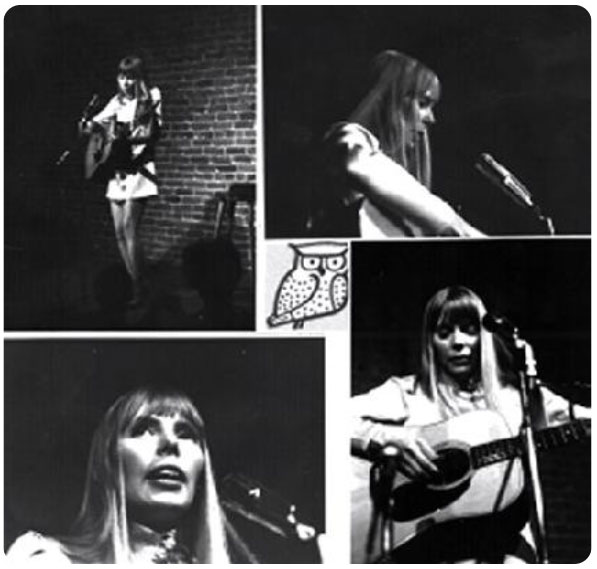

Joni Mitchell playing Le Hibou poster courtesy of Harvey Glatt

"Joni, Graham and Jimi, March 1968”, A chapter from the book We Are As The Times Are - The Story of Café Le Hibou

Used by kind permission of Ken Rockburn and available for Kindle and also in hard/soft cover. Please support the author by purchasing this amazing book: "[Le Hibou] was the locus of hip, the venue for cool, the scene of the scene. Through its doors passed the likes of Neil Young, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, George Harrison, Gordon Lightfoot, Van Morrison, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Otis Spann, Saul Rubinek, Rich Little, Irving Layton, William Hawkins, John Hammond, David Wiffen, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Bruce Cockburn, TBone Walker, Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, Phil Ochs, Odetta, Tom Rush, Jesse Colin Young, Lenny Breau, Kris Kristofferson, Richie Havens, and hundreds more.

By the mid-1960s, the unrelenting, cranked-up electric sounds of rock were beginning to drown out the acoustic folk music that had dominated the North American coffeehouse scene for almost a decade. Bob Dylan had gone electric at Newport in ’65, dragging a large chunk of the folk scene kicking and screaming into the rock world. The year 1967 had witnessed the Summer of Love, and the resulting psychedelia of the Haight in San Francisco was washing across the continent.

But the folkies still had a couple of surprises up their sleeves.

Roberta Joan Anderson had come out of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, with only a guitar and a head full of lyrics and she was doing journeywoman work on the coffeehouse circuit as Joni Mitchell, the surname of the husband she had divorced the previous year.

Despite being unamplified and all alone on stage, her sound and her lyrics were beginning to have a profound impact on the music of the time. In David Crosby’s 1988 autobiography, Long Time Gone , co-author Carl Gottlieb described her this way: “A willowy blonde with big blue eyes and high cheekbones, singing art songs in a belllike soprano with a Canadian accent and accompanying herself on acoustic guitar and dulcimer was not anyone’s idea of The Next Big Thing, but her work was unmistakably different and she was attracting attention.”

In 1967, Mitchell was plugging away at an exhausting tour across Canada and the United States, playing small venues and coffeehouses that demanded two sets of music a night and three sets on weekends. By June, she had reached Ottawa for an extended engagement at Café Le Hibou. The gig also included a live concert at Camp Fortune in the Gatineau Hills, a concert recorded by the CBC as part of its Summer Festival Series. Denis Faulkner booked her for next to nothing. “She wasn’t very well known, so I got her for $150 a week versus 50 percent of the door, and I hired her for three weeks,” he recalled.

During her stay, Mitchell rented a room in a house in the nearby neighbourhood of Sandy Hill, just east of downtown Ottawa. The house was shared by musicians Bill Stevenson and Sandy Crawley; Caroline Petch, who would later become one of Hibou’s managers; and Dan McLeod, who would become one of the publishers of Georgia Straight . She and Stevenson “just hit it off,” he remembered. “I don’t know why. I was younger than her, and, as was the way back then, we sort of drifted into each other’s lives. We spent quite a bit of time talking to each other during that short period of time.”

Stevenson, an accomplished piano player and singer, was just about to hook up with David Grisman and Peter Rowan as part of the band Earth Opera, and would be signed by Jac Holzman’s Elektra Records. Mitchell and Stevenson spent time at a Chinese restaurant on Rideau Street (“She liked the Almond Soo Guy,” he said), and the two of them dropped acid in Strathcona Park, next to the Russian Embassy. Sandy Crawley didn’t recall her being at the house very much but admitted his memory might be faulty “because we were taking LSD every day. For, like, two weeks I remember taking a hit every day with Bill,” he laughed. His memory of Mitchell was of “a very flirtatious and promiscuous girl, but bravely so. I was very promiscuous myself and I made it possible for others to be so. I believed that that was a good thing.”

Ed Honeywell, a young guitarist who had been alternating at Hibou between performing solo on classical guitar and accompanying other musicians, was asked to meet with Mitchell and accompany her on some of her songs at Camp Fortune. “I didn’t know anything about her at all. So I guess Bill Stevenson was sort of minding her; she was staying at his place in Sandy Hill, and I went there to rehearse with her. She played a couple of her things and she uses these weird tunings, these open tunings, which are phenomenal. In those days, I wasn’t playing open tunings, so I very quickly determined that there was no way I was going to accompany any of that with her and I said that. Of course, her stuff is unique—it doesn’t need accompaniment. So I told Tom (the CBC producer) maybe “Both Sides Now” I could do, maybe “The Circle Game,” but the other stuff? Forget it. “Chelsea Morning”? That’s her stuff. So we did the show and she was a real hit. But when she played at Hibou, I asked her about her tuning, so I learned a lot of new tunings from her.”

When the Hibou gig ended, Mitchell continued her tour and, by the late fall, was in Coconut Grove, Florida, playing a club called the Gaslight South. Ex-Byrd David Crosby was also there, buying his first boat, the Mayan . The two met, became friends, and then, in her words, became “romantically involved.”

Prior to meeting Crosby, Mitchell had met Elliot Roberts in New York and he had taken her on as his first managerial client. Roberts and Crosby then shepherded her through the recording of her first album in Los Angeles. Song to a Seagull (originally called Joni Mitchell ) would be released on Frank Sinatra’s Reprise label, part of Warner Bros.

Both Mitchell and Crosby were very conscious of having to protect her singing style and appearance, working hard to make sure her first record presented her as she actually was. According to Mitchell, the record company wanted to “folk rock” her up, but Crosby and Roberts wanted to present her as the cutting edge of a “New Movement.” To pull that off, Crosby, with his Byrds cachet well in hand, told the record company he would produce the album himself. Then he pretty much just kept out of it. That move alone gave Mitchell the control she wanted and maintained for the rest of her career. She has said Crosby did a “solid favour” for her that she never forgot.

So eight months after her original gig in Ottawa, with Song to a Seagull recorded but not yet released, a new manager, and a relationship with a rock star, Mitchell returned for a two-week engagement. This time she was staying at the upscale Chateau Laurier Hotel. The Chateau, with its castle-like turrets, grand ballrooms, and views of the Parliament Buildings, was the hotel of choice for visiting rock stars. It was also just two blocks away from Hibou’s Sussex Drive location.

Her opening night on Tuesday, March 12, was well received by Ottawa Citizen reviewer Bill Fox (who, many years later, would become Brian Mulroney’s press secretary). A student at Carleton University, Fox had been given the task of writing about the new rash of concerts that appealed to a younger audience. He had no illusions that he was a critic—he simply wrote from the perspective of an audience member determining if he had been adequately entertained for the cost of admission. Joni Mitchell passed with flying colours. “Appearing on stage in a rust-coloured mini-dress,” Fox wrote, “Joni opened the set with one of her more famous songs, ‘Urge for Going.’ But the best example of her polished stage presentation occurred as Joni was preparing for the last number of the set. As she was tuning her guitar for ‘And So Once Again,’ one of the strings broke. Undaunted, Joni set the guitar against a stool and sang the number, the story of a young man and his girl who break up when he goes off to war, without accompaniment, something a lesser performer would never have attempted.”

Only three days after that auspicious opening, Joni Mitchell would meet someone who would change the course of her life for the next several years.

It was a mild mid-March evening with a light rain falling when the Hollies played two sold-out shows at the Capitol Theatre on Bank Street. Bill Fox raved about this show as well: “The Hollies are unlike most groups—they can sing,” wrote Fox. The band “proved why they are called ‘a group’s group’ by other British artists.”

After her set at Hibou that night, Joni went to a small party for the band members. Harvey Glatt, his wife, Louise, and Bruce Cockburn went with her. Graham Nash, who was beginning to have thoughts about extricating himself from the Hollies, had been given a heads-up about the young singer from David Crosby but he had forgotten all about it until he saw Joni sitting by herself. “We could see that a thing was happening between Joni and Graham so we left,” recalled Glatt.

He was not mistaken. Nash recalled the night vividly. “I see this woman across the way sitting on a chair with what looked like to me a large bible on her knee, which was intriguing. More intriguing was the fact that she was one of the most beautiful creatures I had seen in a long, long time,” he said.

Because it was an after-concert party, most of the attendees were music or concert business folk and Nash was trying to ignore the incessant chatter of his manager, Robin Britton. “I think he’s just nattering in my ear about business and I’m not listening because I’m looking at this woman. I go, ‘Robin, please, I’m trying to concentrate on this woman!’ He goes, ‘Well, if you’ll just listen to me, I’m telling you that the woman over there, her name is Joni Mitchell, and she wants to meet you because she’s a friend of David Crosby’s.’ I hadn’t been listening to him.”

Nash walked over to the young woman and introduced himself. “She says, ‘Yes, I know who you are.’ And I say, ‘Tell me about the bible.’ She says, ‘It’s not a bible, it’s a music box.’ I think she opened the front cover, which triggered the mechanism, and it played this funky tune that had a beautiful little melody except the last note was either broken or shortened or something, but it was totally out of tune with this beautiful little melody that had gone on. When it came to the end it went, dah dah dee dee… bleep! It was kind of funny, and we started laughing about it and we started talking, and there was obviously a great attraction there, certainly on my part.”

Mitchell invited Nash up to her room at the Chateau Laurier. He remembered the “gargoyles and mythical creatures” on the roof outside her window. “She played me some of the greatest songs I’d ever heard in my life: ‘Nathan’ and ‘Little Green’ and ‘I Had a King’ and on and on… the most incredible songs, and very obviously I fell in love.”

Mitchell’s spell over Nash put him in a bit of a bind with the Hollies’ next tour date. “We were supposed to play in Winnipeg the next day, and I had put in a wake-up call to the hotel receptionist from Joan’s room, put the phone down, and then slept with Joan. I woke up the next morning and something didn’t feel right timing-wise, and I looked at the hotel clock, and it’s like an hour past my wake-up call; and I look at the phone and I realize that in my delirious state I hadn’t put the receiver actually on the phone, so there was no way that they could call me. So now I call the Hollies’ rooms and they’re not there. They’ve gone to Winnipeg. And I’m stuck here and I’m going, ‘Where’s Winnipeg?’ I look at a map and I go, ‘Holy Toledo! This is miles away—this is not like I can get into a cab!”

He somehow managed to make it to Winnipeg to continue the Hollies’ tour and Mitchell carried on with her Hibou gig. But by summer they would be living together in Mitchell’s new house in Laurel Canyon, California, ultimately skirting very close, said Nash, to marriage.

The second significant event for Mitchell that March happened just four days later, on Tuesday the 19th. Harvey Glatt’s Treble Clef Entertainment brought in Jimi Hendrix to play the Capitol Theatre. Tickets sold so quickly that a second show was added at six in the evening, with the originally scheduled show at eight-thirty. Ticket prices ranged from $2.50 to $4.50.

The Capitol was one of those old, ornate, neo-Baroque theatres with gingerbread embellishments and wide staircases to the loges and balconies. The rag-tag, hippie audience seemed somewhat out of place pouring into that staid cavern late that sunny, warm afternoon.

Out front, on Bank Street, the artist Arthur II ran into an old friend who asked if he wanted a ticket to the concert. Arthur wasn’t too interested; he’d heard the first Experience album and thought it was too “out there,” preferring older rock ’n’ roll. But then his friend made him an offer. “He says, ‘I can’t go and I’ve got this ticket,’” Arthur recalled. “Meanwhile, we’re smoking, he’s got this cigarette, and I’m having a puff and he hands me this ticket, I take another puff of this cigarette and I realize it was pot. He’d taken all the tobacco out and filled it with pot and then put tobacco in the end. The first puff was definitely tobacco and then it was, like, Oh! Okay! I looked at this ticket, and I turned around, and he’s not there. I’m standing there in the fucking parking lot with this ticket, high as a newt, within moments. And my friend had disappeared. And I thought, ‘Well, okay, I guess I’m going to Jimi Hendrix.’ I went to Jimi Hendrix and I had one of those little box seats on the side. I was level with the stage. It was fabulous. I was blown away.”

Inside the Capitol, Doug McKeen was preparing to record the concert for Treble Clef. McKeen was a young, ambitious entrepreneur who cobbled together an income by playing records at weddings and birthday parties and doing the sound for the increasing number of concerts that Treble Clef was producing. But that day, his business partner was sick, and he was on his own. This meant that he was simultaneously working for himself and for Harvey Glatt.

“There were only two mikes on stage because there were only two people who were going to sing, and Hendrix didn’t want any more,” said McKeen. “They were a wall of sound. There were Marshall amps and they were all set to ‘max’ because the guy uses feedback in the show. So the mikes had to pick up everything. And the fact that you got his voice was only because of proximity. The sound was so loud. I was wearing a pair of Koss headphones—the ones that if you wore them long enough, your head went to a point, they were that tight—I had those on not plugged into anything and I was in pain. They didn’t allow you to go in the middle of the audience where I should have been if I was doing a mix, but I wasn’t doing a mix that night. I was right in front of one of the Altec A-7s, because that’s the place they put us. We just had an Uher tape recorder tucked underneath the equipment rack.”

There was a second person recording the concert that night as well. Hendrix himself had a large, two-track tape recorder—which was either a Revox, an Ampex, or a Sony, depending on who is doing the remembering—which he placed on the stage in front of him. Sandy Crawley recalls Hendrix “leaning over and starting the clunky tape recorder himself.”

Arthur II wasn’t the only lucky guy that day. Aspiring guitarist Don Wallace also lucked out. Like Arthur, Wallace wasn’t an especially big Hendrix fan—he leaned more toward Eric Clapton and Cream. But he wasn’t about to refuse the good fortune that came his way that day. “I bought a ticket, and it was for the second show, and my ticket was way up in the rafters,” he recalls. “I was standing out in front of the Capitol Theatre—I’m sure kids still do it today, looking groovy before the concert—and a guy I knew had just had a fight with his girlfriend. She went running down the street with him in hot pursuit, and he handed me his ticket. It was in the front row on the left-hand side of the theatre, so I was sitting right in front of Jimi Hendrix in the front row.

“I’m a seventeen- or eighteen-year-old guitar player, with Hendrix about fifteen or twenty feet away on a small theatre riser, not a great big stage. I remember being completely floored. How do you do that with an electric guitar? Nobody did that with a Stratocaster because a Stratocaster was a surf guitar. In the middle of the concert, Hendrix stood back from the mike and said, ‘I need to breathe, I need to breathe.’ Then he went into this four or five minutes of slowly building sound effects. No melody, just sound effects from the guitar. Incredible sounds, I’d never heard anything come out of a guitar like that. That was the intro to ‘Purple Haze.’ I remember leaving the concert that night thinking it sounded like a giant whale breeding under water. It cost me nothing, two bucks, to sit there and watch one of the greatest guitar players of the age.”

During the eight thirty show, Hendrix made a reference to the war in Vietnam, asking why everyone didn’t just come home with “feedback guitars on their backs” instead of guns and rockets, “that’s better than guns.” A bit later in the concert, as he was bent over wailing away on his own feedback guitar, a young woman in the audience reached up and stole his trademark black, wide-brimmed hat with the circular buckles around the crown. Harvey Glatt came to the rescue. “I went out to the lobby and asked various people if they saw who took it,” he said. “They said it was a girl in a yellow raincoat, and I spotted her and I said, ‘You have his hat?’ and she said, ‘Yes,’ and I took it from her and brought it back to him, and he was thrilled.”

At one point near the end of the concert, Doug McKeen was called to the front of the house by Glatt to help with some long-forgotten issue. When he came back, he had a surprise. “While I was up front, Hendrix was basically running by itself. I had left the console, went to see to the thing; when I came back, the tape recorder was sitting there, but the tape’s gone. And that’s the first bootleg that appeared was that tape. No idea who took it, but it did get an excellent review, saying it was one of the best-recorded things. And for the last fifteen minutes, there was no one at the console. So, not bad.”

On October 21, 2001, Experience Hendrix, the corporation that controls Jimi’s estate, released The Jimi Hendrix Experience Live in Ottawa . There is some confusion as to whether that recording is from the missing McKeen tapes or from the tape that Hendrix himself made. Doug McKeen has been told that there was a second mike taped to his stand, but he can’t remember seeing one. He has also read reviews of the bootleg album commenting on the “stereo imaging.” But his recorder was mono, and Hendrix would have needed two mikes, which he clearly did not have. The mystery will likely never be solved.

While Hendrix was ripping into his second show on Bank Street, a few blocks away, on Sussex Drive, Joni Mitchell was preparing to go on stage for the start of the second week of her gig at Hibou. The two had already spoken, as Hendrix noted later in his diary:

Arrived in Ottawa… beautiful hotel… strange people. Beautiful dinner… talked with Joni Mitchell on the phone. I think I’ll record her tonight with my excellent tape recorder (knock on wood)… hmmm… can’t find any wood… everything’s plastic. Beautiful view. Marvelous sound on first show. Good on 2nd. Good recording. Went down to the little club to see Joni—fantastic girl with heaven words.

So after two blistering shows that would have exhausted any normal person, Jimi Hendrix decided to go to Le Hibou and tape Joni Mitchell’s performance.

Bill Hawkins was at Hibou and Joni asked him if he would go pick Hendrix up. Hawkins drove over in his old Borgward (a vintage car from a German company that went out of business in the early sixties and ended up being bought by the Mexican government). “I picked him up at the Capitol Theatre after his gig there and brought him down to Le Hibou with this huge big reel-to-reel so he could record her.” Hawkins found Hendrix to be “a very laid-back guy,” who was impressed with the Borgward, and the trip consisted mostly of them talking about the car.

Hawkins dropped Hendrix off in front of Le Hibou, where he was joined by a couple of record company reps. John Russow, the relatively new owner of the coffeehouse, was taking admission money at the door. Inside the front entrance of Hibou was a little square foyer with a pay phone on one wall, and opposite was the table where Russow sat.

Russow is the first to admit that, as a trained architect who had been involved in the folk club scene for a couple of years, he was neither aware of nor interested in the rock scene. So he was underwhelmed by what was to happen next. “Jimi Hendrix came with his manager and an entourage of people,” Russow recalled. “He came in, I was at the front taking money, and one of them said, ‘This is Jimi Hendrix.’ And I said, ‘Well, that’ll be two-fifty.’ And he said, ‘But that’s Jimi Hendrix!’ And I said, ‘I don’t care if it’s the king of whatever, it’s two-fifty to get in.’ Hendrix was standing over by the phone in the corner while this more slick manager was trying to convince me and he was getting more and more agitated and angry. So I said, ‘Well, if you can’t afford it, I’m afraid there are a lot of people who want to come in.’ And then, finally, Jimi Hendrix, who was a very shy guy, came over and said, ‘Forget it, forget it. Just pay, pay the thing.’ The guy then threw down a twenty-dollar bill and said, ‘You asshole, keep the money.’ I said, ‘I will. Thank you very much.’”

Young Art Petch, who was due to graduate from high school that year and had managed to get a job working in the kitchen at Hibou through his older sister, Carolyn, had gone to the Hendrix show and had been disappointed. “I was a big Hendrix fan; who wasn’t? I remember sitting there thinking it was good but it wasn’t as good as my stereo. I don’t know what it was… I enjoyed it but it wasn’t special.” His sister asked him if, after the concert, he would deliver a sweater to Mitchell in the upstairs green room. He dutifully got the sweater and entered the club through the back door and the kitchen and started up the stairs. “I look up and there’s Jimi Hendrix standing there! He was standing at the top of the stairs and the feeling that I got was that he had just arrived and was introducing himself. I had seen Joni perform before at Hibou and I probably didn’t appreciate how good she was at that time and I wasn’t particularly in awe of her.”

Meanwhile, Arthur II had emerged, transformed, from the Hendrix concert and, still high, decided to continue his evening at the coffeehouse. “I get outside and I think, ‘I hear Joni Mitchell’s down at Hibou,’” he remembered. “So I went down and I couldn’t get in. It was full. I thought, ‘Well, I know how I might be able to get in.’ So I walked around to the back, and sure enough, somebody came out the back, and I went in and I’m standing there in the little alleyway between the main room and where you go up to the bathroom and the green room, and I couldn’t move either way. I could see the stage, okay, that was great. Nothing has started yet.”

When it came time to go on, Mitchell descended the narrow stairway past Arthur’s vantage point. “I hear all this noise and here she comes down the stairs, in her little miniskirt and looking like an angel and she walks by me and it’s, like, ahhhhh, take a deep breath, this is awesome. So that was a big night for me. Joni Mitchell and Jimi Hendrix, and I was high, and it was all for free.”

Hendrix’s presence in the club almost went unnoticed, but an eagle-eyed Jan Morrison spotted him right away. Morrison, who frequented the club, went that night with her future husband and some friends. They had been out drinking and decided to go see Joni Mitchell, a bit steamed that there was a $2.50 cover charge. They took their seats at one of the tables, and Morrison spotted Hendrix who, it turns out, was sitting just a few feet from where Arthur II was hiding in the hallway. “I said, ‘That’s Jimi Hendrix!’ and the people I was with said, ‘No, it isn’t! You’re crazy.’ And I said, ‘It is Jimi Hendrix!’ So I walked over to him and said that thing you say to famous people: ‘You’re Jimi Hendrix!’ as if they don’t know,” she laughed. “And he said, ‘Yes, I am.’ And I said, ‘I am so delighted to meet you, can I shake your hand?’ And he said, ‘You sure can.’ And he was taping Joni. We were near the front door, and he was stage left, close to the front, where the musicians used to hide out in the teenytiny green room that was as big as your toe. But nobody was looking at him. I don’t think anyone realized it was actually him. You have to remember that pictures of Jimi Hendrix at that time were always acid influenced. He had way less hair than he did on the cover of his albums and it wasn’t purple and bright green.”

Harvey Glatt, who had come down to the coffeehouse after the concert at the Capitol, had a vivid memory of Hendrix taping Mitchell. “He was sitting at the side of the stage while Joni was singing; he had headphones on and he was recording her—I can still see him.” Bill Hawkins, who had parked his Borgward and come into Hibou, also saw Hendrix at the side of the stage. “He was hunched over the tape deck and the only comment I can recall was him saying, ‘angel words,’ over and over. I had to concur: She was a goddess wherever she was.”

After Joni’s final set, the group repaired to the Motel Deville on Montreal Road in Eastview for a party; or, as Hendrix put it succinctly in his diary: “We all go to party—O.K. millions of girls.”

Despite Bill Hawkins’s recollection of the party’s being “seedy like the guys from the record company that John [Russow] forced to pay,” Eastview was chosen because, as an incorporated city not part of Ottawa, its bars could stay open later. It was also the site of one of the first discos in the area.

Sandy Crawley, Joni Mitchell, Harvey Glatt, and Bill Hawkins all squeezed into a car for the ride to the motel. Hendrix and his two band mates, Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding, arrived together. Crawley remembered Redding and Mitch Mitchell being “speedy and tense and not too happy.”

Bill Hawkins pulled out his guitar and, sitting cross-legged on the floor with Joni and Jimi, proceeded to play a new song he had written, called “Scorpio,” because both of the singers were born under that sign. As he told Ottawa Citizen journalist Chris Cobb, “I wrote songs for every zodiac sign. Jimi asked me why, and I told him it was a good way to pick up girls. I was trying desperately to hustle Joni… that night she looked so radiant and was smiling a lot. She was always a little full of herself, but why not?” Sandy Crawley remembered Joni pitching a song to Hendrix as well and her being “all flirty flirty.” Hendrix told Hawkins that he was a bit tired but that the concert had gone well. They spent the rest of the time talking about guitars. “He wasn’t at all bent out of shape that night,” Hawkins said. “Which was more than I can say for myself.”

The party went long into the night, but the next day, for Jimi Hendrix, it was back on the road, while Mitchell had to prepare for another show at Le Hibou. In his diary, Hendrix mentioned her one last time: “We left Ottawa City today. I kissed Joni goodbye, slept in the car awhile. Stopped at a highway diner. The real thing. I mean a real one just like in the movies.”

The Ottawa Citizen that day carried Bill Fox’s review of the concert with the headline, “Guitar Wizard Jimi Hendrix Bombs at Capitol Theatre.” Fox called the show “unorthodox and unpredictable” and said that it “failed to live up to its advance billing.” Looking back at it, Fox, who ironically had always been a huge Hendrix fan, thought it was a case of having too high expectations. But the response to his review was immediate and unpleasant. “People just went wild,” he said. “The then editor-in-chief, Christopher Young, was a very distinguished guy, a distinguished foreign correspondent, and he came down to me and said, ‘Who is this guy? What have you done?’ People were really upset, and it was intensely personal; it was unbelievable.”

After the Hibou run, Mitchell went to Montreal before heading to Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, for a performance there in early April. Le Hibou manager, Catherine Boucher, and her partner, Merité, met up with her in Montreal. “She’d never been there, and we said we’d show her around,” Boucher recalled. “She wanted to go antiquing, so we walked her around old Montreal, and she bought a grandfather clock that she had shipped to California. Merité was adopted and, for some reason, they got talking about it. So we knew that she had this daughter. She told us that she had given up this daughter for adoption, so that connection was made with my friend, who was adopted.”

Later that month, Song to a Seagull was released and Joni Mitchell, twenty-four years old, began her climb to musical legend status. Two-and-a-half years later, on September 18, 1970, Jimi Hendrix died of a reported accidental overdose of sleeping pills combined with wine. He was twenty-seven.

Copyright protected material on this website is used in accordance with 'Fair Use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner(s). Please read Notice and Procedure for Making Claims of Copyright Infringement.

Added to Library on January 28, 2017. (37121)

Comments:

Log in to make a comment